Plant pathology (plant pathology, phytopathology) is an applied discipline that studies the pathogens, occurrence, development, and prevention of plant diseases. It takes plant diseases as the research object, explores the causes of disease, or explores the process of infection and symptom appearance in anatomy, physiology, or biochemistry. In order to establish methods for disease prevention and treatment, it also studies the environmental conditions for the formation of pathogens, the transmission routes of pathogens, and the diagnosis of diseases. In addition, it studies the pharmacological effects of disease prevention agents on pathogens or plants, as well as a wide range of fields related to all plant diseases.

Background

In the 18th century, people gradually realized the infectiousness of plant diseases and the microbial pathogenicity of plant diseases. In the early 19th century, mycology gradually developed on the basis of plant morphology and plant taxonomy, and the nature of fungal pathogens was first studied and recognized. In 1775, M. Tillett proved that bunt was contagious. In 1807, B. Prevot proved that the disease was transmitted by spores. Between 1847 and 1865, L. E. Tirana studied the morphology and life history of ergot, smut and rust. Between 1853 and 1866, Heinrich Anton de Bary, in further research on smut, rust and potato blight, explained the pathogenicity and pathogenesis of pathogens to plants, and proved the polymorphism in the development of fungi and the parasitic phenomenon of rust. His multi-faceted research on fungal diseases and pathogens of some important crops laid the foundation for plant pathology. The book “The Causes and Control of Crop Diseases” written by J. Quene in 1858 summarized the understanding of the occurrence of plant diseases and pathogens during this period, proposed the relationship between environmental factors and the occurrence of plant diseases and methods of disease prevention and control, marking the birth of plant pathology.

In 1888, Pierre Marie Alexis Millardet created Bordeaux liquid, which successfully prevented and controlled grape downy mildew and pioneered the chemical control of plant diseases. In 1866, M.C. Voronin observed bacteria in plant nodules, which was the first time that bacteria were found in plants. In 1879, T.J. Burrill discovered that amylopectin was caused by bacterial parasitism. In 1899, E.F. Smith conducted a systematic study on bacterial plant diseases and developed the field of bacterial diseases in plant pathology. In 1879, Mayer discovered tobacco mosaic and noted the infectiousness of the disease. D.I. Ivanovsky studied this disease and proved in 1892 that the pathogen was a microparticle in the sap of diseased leaves, which could pass through bacterial filters and was different from bacteria. In 1898, M.W. Beijerinck called this type of pathogen a virus to distinguish it from bacteria, thus pioneering a new field of viral pathogens in plant pathology. In the late 19th century, plant pathologists used hybridization to select new asparagus varieties that were resistant to rust. In 1902, W.A. Orton selected cotton varieties that were resistant to wilt, thus developing the study of the immune mechanism of plant pathology and the prevention method of disease-resistant breeding.

Scientific research achievements

Chinese plant pathology is one of the earliest disciplines in biology. In 1917, plant pathology courses were set up in higher agricultural and forestry teaching. The Chinese Society of Plant Pathology was established in 1929. From the 1920s to the 1940s, the pioneers of Chinese plant pathology, such as Dai Fanglan, Deng Shuqun, Zhu Fengmei, and Yu Dafu, made contributions to the study of the morphology and classification of Chinese fungi, fungal, bacterial and viral diseases of major crops, and disease-resistant breeding. They established laboratories in several higher agricultural colleges and research institutes, trained many plant pathologists, and laid the foundation for the development of Chinese plant pathology.

Research content

Plant diseases

When a healthy plant is disturbed, resulting in local or systemic abnormalities in the physiological mechanisms of organs and tissues, the plant itself shows symptoms, and the substances extracted from the diseased parts have the symptoms of the corresponding pathogens, then plant diseases have occurred. Factors that interfere with the normal physiological mechanisms of plants are mainly exogenous, and internal factors lead to genetic diseases; some exogenous factors are non-biological and some are biological. Therefore, according to the nature of the inducing factors, plant diseases can be divided into two categories: non-infectious diseases and infectious diseases.

Non-infectious diseases:

In the long evolutionary process, plants have gradually adapted to various changing environments and developed strong adaptability. However, there is a certain limit to the adaptability to various environmental factors. If some physical factors such as light, water, temperature or chemical factors such as nutrient elements in the environment where the plant is located are imbalanced or the living environment deteriorates, and the plant is continuously affected, and its intensity exceeds the tolerance limit of the plant, it will have an adverse effect on the growth and development of the plant, disrupt normal physiological and metabolic activities, and even cause serious damage to the plant, causing the plant to show abnormal physiological and appearance and produce pathological changes.

Infectious diseases

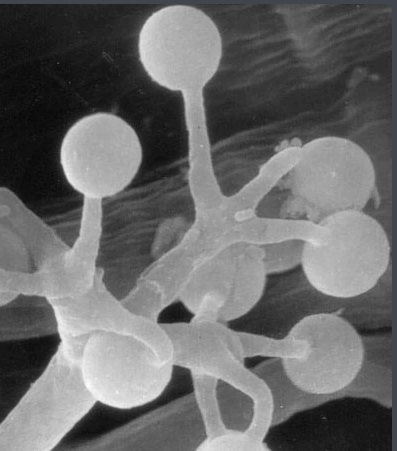

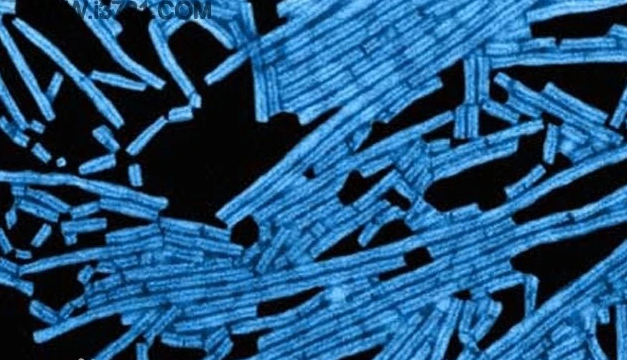

Infectious diseases are infectious diseases in which plant pathogens fight each other under the influence of external conditions and cause plant diseases. Common plant pathogens include fungi such as smut, rust, powdery mildew, etc.; oomycetes such as pythium, downy mildew, etc.; prokaryotes are mainly bacteria such as Agrobacterium, mycoplasma, chlamydia, etc.; viruses such as potato virus Y, yellow virus, tobacco mosaic virus, etc.; higher plants such as dodder, broomrape, etc.; protozoa such as nematodes. Among them, diseases caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses, mycoplasmas and nematodes are more common and serious, especially fungal diseases, such as rice blast, wheat rust, cotton wilt, etc. The physiology, ecology, proliferation method and life history of various pathogens, as well as the way, path and period of infection of hosts are different.

Pathological analysis

For pathogens to cause disease in hosts, they must first have the opportunity to come into contact with the host and invade the host body. Pathogens are spread by wind, water, soil, seeds and animals, reach the surface of the host body, and invade the host body through natural holes (such as stomata, lenticels, nectaries, etc.) or wounds (such as mechanical trauma, insects and human-caused wounds) on the host body. During the infection process, the host shows mechanical and functional resistance and sensitivity mechanisms. The cuticle and epidermal cell walls on the host surface both play a role in resisting the invasion of pathogens. The structure of some natural openings is also not conducive to the invasion and development of pathogens, and some compounds in some hosts, such as phenols, tannins, and ethylene, can limit or kill the invaded pathogens. However, the most important thing is the host’s own disease resistance or susceptibility, which can range from self-immunity to absolute susceptibility. Disease resistance means that the host can still grow relatively normally after being infected with pathogens. Do not suffer much economic loss due to disease. Therefore, disease-resistant varieties of crops are often used to avoid losses caused by some common local diseases.

The occurrence of diseases is the result of the interaction between pathogens and hosts, and thus has become one of the most important research contents of plant pathology. The hypersensitivity of host plants can cause pathogens to quickly kill local tissues of the host after invading the host, forming necrotic spots, which limits the continued development of pathogens in the host; or stimulate the formation of obstacles (such as cork layer) in the host tissues to curb the spread of pathogens; or cause physiological abnormalities in the host, such as obstacles in the mechanism of absorbing or transporting water, which causes the infected part to wilt and restrict the development of pathogens. Therefore, the hypersensitivity of host plants to pathogens also plays a role in disease resistance to a certain extent. Plants have natural immunity to pathogens, but also show acquired immunity. After some pathogens (such as viruses) infect the host, the host shows disease resistance and no longer shows symptoms due to infection. At present, the use of inactivated pathogens as vaccines to inoculate host plants to make them immune has achieved initial results in preventing the occurrence of diseases. For example, injecting heat-passivated tobacco wildfire bacteria into healthy tobacco plants can protect tobacco from diseases. Parasitic fungi can induce the host to produce plant protection factors, which are antibiotics with disease resistance.

The relationship between pathogens and hosts is greatly affected by environmental conditions. The occurrence and development of plant diseases must have suitable environmental conditions. Temperature, humidity, light, soil pH, water, nutrient supply, etc. all affect the occurrence and severity of diseases to varying degrees.

The parasitic nature of pathogens is different: there are obligate parasites, facultative parasites and facultative saprophytes. The vast majority of fungal and bacterial pathogens are facultative parasites, and pathogenic nematodes are also facultative parasites. Viruses, viroids, mycoplasmas, and chlamydia are all obligate parasites. The host range of pathogens varies. Some only parasitize on some species in one genus or one family, while others can parasitize on plants of many families. The certain relationship between pathogens and hosts is the result of genetic adaptation in biological evolution.

Prevention and control measures

Eliminate pathogens: Eliminating pathogens or eliminating pathogens is to prevent pathogens from entering disease-free areas. Establish a quarantine system, formulate quarantine regulations, and conduct external quarantine to prevent the introduction of pathogens from abroad. Internal quarantine prevents the spread and expansion of diseases.

Eliminate pathogens: Eliminate pathogens to eliminate existing pathogens on plants, farmlands, and gardens. For example, implement farm hygiene to remove diseased plants, eliminate alternate hosts, remove weeds, burn diseased plant residues, and deep ploughing and crop rotation, apply surgical operations, etc.

Protect the host: Protect the host to set up barriers to contact between the host and the pathogen. For example, use chemical protection, spray and spread fungicides on the host to kill pathogens that will or have come into contact with the host. Use soil disinfection technology to prevent the spread and invasion of soil-borne pathogens. Biological control using antagonistic fungi or bacteria to control pathogens is also an area that needs research and development.

Utilize host disease resistance: Utilizing host disease resistance to control plant diseases is an effective and economical measure. Therefore, disease-resistant breeding is also an important part of plant pathology.

Specific disciplines

Plant pathology is derived from botany, and has developed through the mutual penetration of plant physiology and microbiology. It is also closely related to agronomy, protozoology, soil science, meteorology, genetics, biochemistry and other disciplines. Plant bacterial diseases, plant virus pathology, chemical control of plant diseases, plant disease resistance breeding and immunology, and ecological plant pathology are its main derived branch disciplines.